Roosa and related families of New Netherland

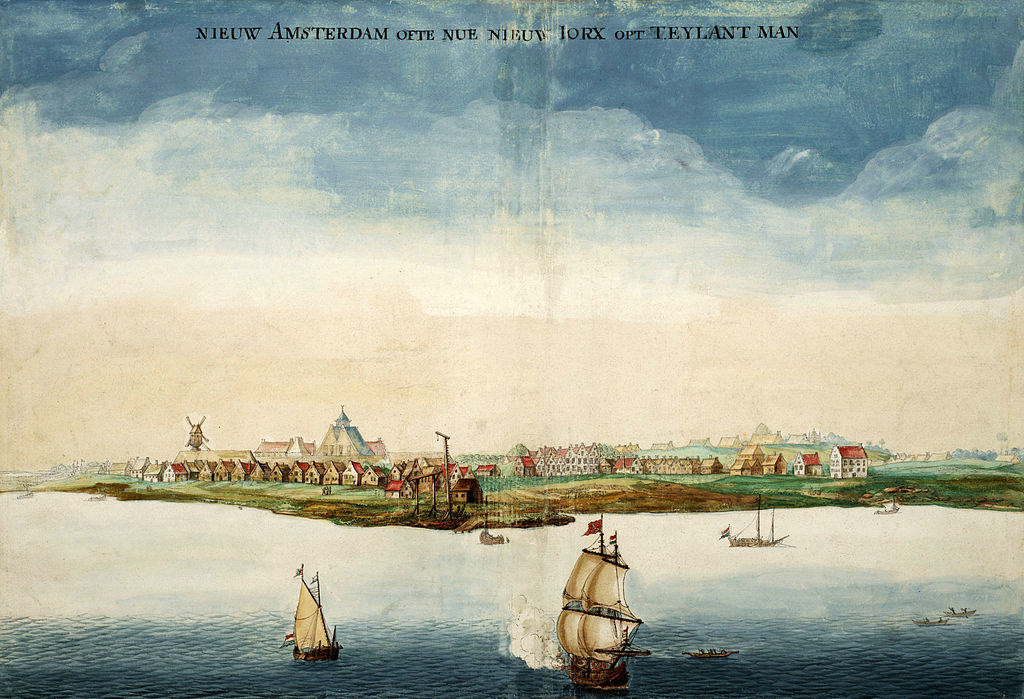

View of Nieuw Amsterdam by Johannes Vingboons (1664), an early picture of Nieuw Amsterdam made in the year when it was conquered by the English under Richard Nicolls. In 1664,just three years after the Roosa family arrived, New Amsterdam passed to English control, and English and Dutch settlers lived together peacefully. In 1673, there was a short interruption of English rule when the Netherlands temporary regained the settlement. In 1674, New York was returned to the English, and in 1686 it became the first city in the colonies to receive a royal charter. After the American Revolution, it became the first capital of the United States. via Wikimedia Commons

Direct ancestors of Jonathan Cline are in bold.

The Roosa family had lived in Ulster county, New York since 1661 when Heyman Aldertse Roosa and his family packed up their belongings and boarded a ship in Holland, then made the long journey to first New Amsterdam and then on up the Hudson River to the small settlement of Esopus.

" The passenger list of the "Bontekoe (spotted cow) of April 15, 1660 contains the name of Aldert Heymans, Agriculturist, from Herwynen, Gelderland, who came with his wife and eight children. Arie, 17, Heyman 15, Jan 14 Eyke 9, Maritje 8, Neeltje 7, Jannetje 4, and Aert 2. (doc, Hist N.Y. III p 56). No more colorful personage lived at Esopus and his name appears more frequently in the old records of the settlement than that of any other man. That he occupied an influential position in the founding of the city is recognized.

There were several other immigrants from Netherlands that came at about the same time and Esopus was growing quickly with all the many new immigrants. Most of them were Huguenots or Walloons who left their native France and had moved to Germany, England or Holland to escape religious persecution from the Catholic church. There had been Indian wars off and on for years but a recent truce had been signed and it was peaceful when the Roosa family arrived.One of our other of our ancestor's families that left Holland were , Mathese Blanchan and his two son in laws families, Antoine Crispel and Louis du Bois. The Dutch ship Gilded Otter in the spring of 1660 brought the Blanchan and the Crispel families over to the little town of New Amsterdam. It was nestled upon the lower end of Manhattan Island. At this time it consisted of two hundred poorly constructed houses giving comfort to some fourteen hundred people. They did not stay long in New Amsterdam and taking counsel of their Walloon countrymen, and getting permission from the governor they went up the Hudson river to Esopus. They were soon joined by the other son-in-law's Louis Du Bois family which came to New Netherland on the ship St. Jan Baptist arriving August 6, 1661.

The spot where after many wanderings our refugees had finally found a home was chosen. It was a short distance from the river and must have reminded them of the Rhine River back home. The plateau upon which the village Wiltwyek stood skirted by Esopus creek. From the banks along the palisades protecting it that had been constructed, the settlers overlooked the fertile lands occupied by the farms of the white men and also the patches upon which the Indian women still raised their crops of maize and beans. The beautiful valley of the Wallkill opened toward the southwest. On the north the wooded slopes of the Catskill mountains were visible.

This is where the Roosa's and Mathese Blanchan and his two sons-in-laws families settled. Meanwhile another settlement started up about a mile west of Wiltwyck. The houses and barns were built inside a fortified enclosure where 15 families were protected from Indians but at this time were peaceful. The Indians though felt this new settlement was on land they still owned and also the governor had sent some of the Indians who had previously caused problems to the island of Caracoa. These two facts plus the selling of Rum to the Indians took away their reason and in time intensified their worst passions.

More Huguenot and Walloon Ancestors

Tjerck Claessen De Witt emigrated from near Esens in Ostfriesland (today the northern coast of Germany) in the early or mid-1650s. Three siblings joined him over the next few years—first a sister, then a younger sister and brother when they got old enough to leave home. The brother, Jan (Tjerck’s only full brother), traveled back and forth from North America to Europe frequently.

On 1 October 1658 (FOCM, p. 410), Eldert Gerbertsen complains that “T’Jerck Claessen” has promised to deliver 200 logs, each at least 6 feet in circumference (about 2 feet thick, or 60 cm); Eldert says he doesn’t have the logs yet, and it’s a big deal to him. Tjerck agrees that he made this promise, and he agrees to get the logs hauled out within two weeks, and not to do any other work until this is done. This gives some suggestion of what Tjerck was doing for a job while he lived in the Fort Orange area.

He first settled in Fort Orange, Beverwokck now Albany but by 1660 Tjerck settles for good in “the Esopus,” an area around present-day Kingston, New York, midway between Albany and Manhattan, where he first appears to live in the town of Wildwyck but eventually starts farming a bit further south, near what becomes called the “Nieuw Dorp” (New Village) and today is called Hurley. (The stone house he eventually built on his land still stands, with several extensions added later, on the banks of the Esopus Creek.) Tjerck, who apparently was making a living from going into the forest and pulling hewn trees out for construction in town, would have known that he was even more exposed to attack than villagers who stayed near the fort all day. It is entirely possible that he worked directly with native people. We know that when he marries in 1656, he picks the daughter of a man (Andries Lucassen) who had translated between European and North American speakers for previous expeditions, and his brother-in-law (Jan Thomasen, based in Beverwijck) is also conversant in local languages. Tjerck was farming in Esopus, 140 or 145 acres (about 57 hectares), a little under a quarter-section.

On 26 December 1660, in Wildwyck, the day after Christmas, a small collection of settlers take Communion for the first time in the brand new church. Most of these are people we will see frequently in the records of the town over the years to come, many of them figuring in our ancestors lives in the little frontier village as it grows: Domine Hermanus Blom (preacher) and his wife Anna, Jacob Joosten, Jacob Burhans, Matthew Blanchan and his wife Madeline Jorissen, Antony Crespel and his wife Maria Blanchan, Andries Barentsen and his wife Hilletjen Hendricks, Margriet Chambrits, Geertruy Andriessen Schout Roelof Swartwout and his wife Eva Swartwout, Cornelius Barentsen Slecht and his wife Tryntje Tyssen, Albert (sometimes Allert or Aldert) Heymanse Roose and his wife Wielke DeJongh. Thir names are inscribed in a memorial plaque today in the Old Dutch Church in Kingston, not on the same site as the original chapel inside the stockade, but the same continuous congregation nonetheless. Names in bold are direct ancestors of Jonathan Cline.

A new town was then built, as the few dozen lots in Wildwyck were taken. This was fertile farmland (and still is 1918?), and it is not clear how well the Esopus tribes understood the Europeans’ intent when they first arranged to use the land, but apparently they were willing to tolerate sharing their good fields with some immigrants. When the Dutch started building a wall around their second new village, though, the natives started raising some concerns. On Tuesday 5 June 1663, the settlers reported, they let the “Indian Sachems” know that they wanted to meet “to renew the peace” When the settlers let the indian leaders know that Stuyvesant wanted to meet with them, and they responded that a peaceful way to meet would be in the field outside the town, unarmed. But on Thursday 7 June 1663, just before noon, they instead mounted a surprise attack, apparently carefully organized in advance.

They came in amicably enough through the open gates of the village, carrying corn and beans as if to trade, and in several bands they made their way through the village. At the same time, a separate group of Esopus must have been on their way to the (still unfenced) new village, not quite three miles away to the southwest. They torched the Nieuw Dorp, attacking the Europeans there. A few settlers got away on horseback and rode for Wildwyck; they came in through the main gate and raised the alarm, at which point “the Indians here in this Village immediately fired a shot and made a general attack on our village from the rear” (p. 39), killing, starting fires, and taking prisoners.

The wind at the time of the attack was coming from the South, so the first fires were set on the south side of the village. “The remaining Indians commanded all the streets, firing from the corner houses which they occupied and through the curtains [the city’s palisade wall] outside along the highways, so that some of our inhabitants, on their way to their houses to get their arms, were wounded and slain” (DHSNY IV p. 40). The wind shifted, saving many houses from destruction. The attack was over almost as soon as it had started, so rapidly “that those in different parts of the village were not aware of it” until they saw the wounded. The village was not large (only a few dozen houses, a handful of city blocks), but many of the farmers were out in the fields when the attack took place, “and but few in the village.”

In or near the village at the mill gate were Tjerck Claesen de Witt, with his neighbor and fellow town council member Albert Gysbertsen and two servants; the Schout, Roelof Swartwout, was at his house with “two carpenters, two clerks and one thresher,” Cornelis Barentsen Sleght was home with one son; the Domine was home with “two carpenters and one labouring man,” and there were “a few soldiers” at the guard house. At the gate closer to the river were Henderick Jochemsen and “Jacob, the Brewer, but Hendrick Jochemsen was very severely wounded in his house [by the guard house; see below] by two shots at an early hour. These twenty or so men chased the attackers off.” Thomas Chambers, like Tjerck a Schepen, “who was wounded on coming in from without, issued immediate orders . . . to secure the gates; to clear the gun and to drive out the Savages, who were still about half an hour in the village” (p. 40). Men who had been working in the fields arrived back at the village, “and we found ourselves mustered in the evening, including those from the new village who took refuge among us, in number 69 efficient men, both qualified and unqualified.” Immediately work began on repairing the village wall.

In a short amount of time, the attackers had killed 12 men in Wildwyck (including one slave and three soldiers), four women, and two children. Eight men were wounded, one mortally. Many of the dead were apparently burned alive in homes and workshops; a few were killed in front of their homes or in the fields near the village. Five women were taken hostage, and five children. In the Nieuw Dorp three men were killed, and the prisoner count included one man, 8 women, and 26 children. Twelve houses were burned in Wildwyck, and “The new village is entirely destroyed except a new uncovered barn, one rick and a little stack of reed” (p. 44). Domine Blom notes also “a large number of animals” were killed, which has a profound effect on village life and economy, as well as food supply for both villagers and the soldiers who will soon arrive to protect them (DRCHSNY XIII p. 373).

Domine Blom described the scene in an 18 September 1663 letter to the Classis of Amsterdam (Corwin, Ecclesiastical Records, I, 534-35, as cited by Marc B. Fried in The Early History of Kingston & Ulster County, N.Y., p. 63): “There lay the burnt and slaughtered bodies, together with those wounded by bullets and axes. The last agonies and the moans and lamentations of many were dreadful to hear. . . . The burnt bodies were most frightful to behold. A woman [likely Lichten Dirreck’s wife] lay burnt, with her child at her side, as if she were just delivered. . . . Other women lay burnt also in their houses; and one corpse with her fruit still in her womb [Tjerck’s sister Ida], most cruelly murdered in their dwelling with her husband and another child [Jan Albertsen Van Steenwyck and their toddler who had accompanied them to Esens and back].”

Later on he filled in even more language: “the dead bodies of men lay here and there like dung heaps on the field, and the burnt and roasted corpses like sheaves behind the mower”.

The night of 7 June 1663 must have been a somber night on which to stand watch. Of 85 men in town, 15 had been killed and one captured. Nobody could have known where the attackers had vanished to in the dark thick woods, or when they would attack again. Against a continent of towns and villages filled with people who spoke unknown languages and kept unknown alliances, the handful of European families knew only that they were badly outnumbered: They had too many people to evacuate in ships, even if they could get to the riverside, and trying to escape over land would mean hiking directly into the territory of the attackers. (As we see later, they did not even know, at the time, where the attackers’ village was.) The smell of freshly burned wood clings to clothes and skin, and on this night—smells seem stronger in the dark—it would have mingled with the smells of the killed villagers and animals that had been left in the flames by the attackers. Everyone had lost family members, friends, churchmates, people with whom they had argued, worked side by side, shared a history.

Tjerck had been in the village when his sister had been killed, together with her husband and their toddler daughter. (A soldier was killed at their house too, Dominicus; the record doesn’t show whether he was there to buy shoes or to protect them in the attack.) Tjerck’s wife was evidently safe, and his younger sister and brother who had arrived a few short months ago, but his eldest daughter had been snatched and whisked off to an uncertain fate. Taatje DeWitt was born at Albany about 1659 She was carried off by Indians at the burning of Kingston in 1663 and later rescued. In !677 she married Matthys Matthyssen (Van Keuren) She is a direct ancestor of Jonathan Clines.

Tjerck bore responsiblity in this great wilderness not just for his wife and family but also for the whole village; he had been named one of the council members (the Dutch word is Schepen, and it is translated “commissary” in some translations, “magistrate” in others), and he was one of the officials who signed the letter sent on Sunday 10 June to Manhattan reporting the attack, together with a list of names of those killed and taken hostage.

Louis Du Bois has a wife and three children captured in the Esopus raid; Matthew Blanchan had two children taken; Aert Pietersen Tack's house was destroyed along with twelve other houses and the church. Aert's wife is a direct ancestor. Two of Albert Roosas children were taken captive. His oldest daughter Eyke and and one other. They were later recovered. Evert Roosa,son of Albert was baptized 26 Oct 1679 in Kingston, Ulster, New York, and married Tietje van Etten (the daughter of Jacob Jansen van Etten and Annetje Adriaens-see Van Etten family) 10 May 1702 in Kingston, Ulster, New York, lived in Hurley, Ulster, New York, will dated 5 Mar 1726/7 and proved 3 May 1749.

Evert Pel's son Hendrick was one of those carried off. He was not found until a year and a half later. He married an Indian girl, had a child and lived with the Indians the rest of his life. There are lengthy details about what happened to the survivors from these two towns that were attacked and what the authorities did to try and find the captives which can be found online with references below. Then there is this note on Albert Heymans Roosa that I started the article on that I found interesting so will include it now: Albert Heymans Roose: No Ordinary HotheadYou can’t tell the players without a scorecard: Albert Heymans Roosa, along with being a member of the church consistory—at times the only member—also has previously been appointed by Stuyvesant as one of the schepens on the town council; he’s not a nobody. (His term as a town council member ended right before the attack.)

He had received a patent for land in the New Village (Nieuw Dorp), which was completely destroyed in the attack; we can guess that he was one of those who had built a house there already. Stuyvesant has appointed him as one of three “overseers” of the new village; it was too small and new to have a full town council yet (see Fried, Early History, p. 55).

Two of his children were taken in the attack. He has waited now a month to see any action taken against the attackers, who haven’t been seen since they melted into the woods with their captives. Instead this bureaucrat sent up from Manhattan insists on patiently chatting with the Indians he has detained. Eventually he gets one of his daughters back on December 3 (see Fried, p. 104), six months after the attack. As late as the following March his other daughter is still unaccounted for; see Fried, p. 107.

After the English takeover of the colony, Roosa is later involved again in conflict with troops quartered in town (Tjerck also is abused by Brodhead and his troops, at roughly the same time); as Fried notes (p. 113), Roosa is sometimes a hero, sometimes a hothead.

In particular see 7 June 1667 (Kingston Papers p. 251, 28 May Old Style), when Wyntie, Allert’s wife, “requests a certificate” from the town council, something along the lines of a letter of recommendation, “concerning the conduct of her husband here at Wildwyck.” Rather than an effusive, flowery description of what a good guy he is, the council describes in some detail what a nuisance he has sometimes been, mentioning only in passing (or in contrast) that he had actually served on the council: 1) He had Pieter Van Hael arrested in 1662, illegally, because Pieter had said he “did not get full weight of some butter received” from Allert; 2) In 1663, he opposed Stuyvesant’s order regarding looking after the town cattle, “on which account an uprising among the burghers could easily have originated.” The certificate goes on to note that after the War Council and town council had promised safe passage “to two highland savages,” Allert went after them “with a loaded gun for the purpose of shooting them dead,” and that on 14 February 1667, “when the burghers here were tumultuous,” Allert “treated [the council] very contemptibly by despising our authority . . . and furthermore has often behaved disrespectfully in opposing decrees.” See further discussion of the conflicts between the town inhabitants and the British garrison, but not all of Albert’s disagreeable behavior might be blamed on unjust provocations of figures of authority.

On this fifth Sunday( 8 July) since the attack, at least the villagers could hope for protection in the fields as the harvest began, but no kidnapped family members had yet been returned to their homes.

And here is another mention of one of our ancestors, Cornelis B Slecht, Sergeant of a military company. He was in Esopus in 1655 and was from Woerden, Holland. He signed an agreement with Governor Stuyvesant to build a stockade and to make peace with the Indians. His son was captured, 1659 and tortured to death and his daughter was captured in the 1663 raid and made to marry an Indian.

On 9 October 1663, Cornelis Barentsen Slecht, “representing his son Hendrick Cornelissen Slecht,” says he is not required to comply with these rules, adding that the only council with proper jurisdiction here is “the Supreme Council” in Manhattan. (Slecht is the one whose wife called Heer de Decker a bloodsucker; see her court case above.) He also refuses to cooperate with the court in trying to sort through the inventories of the people who died without heirs. The court orders him to be confined until he agrees to cooperate. (While the court is still sitting, apparently a long session, he sends a written request to be allowed permission to return home to check his accounts for the estate inventory;)

In council at this 23 October 1663 session (Kingston Papers, p. 91), Tjerck also makes the complaint against Evert Pels that Pels “at harvest time caused one of [Tjerck’s] pigs to be shot.” Pels demands proof. The court instructs Tjerck to produce this proof. Both of these men are ancestors of ours. In September 1664 the British took control of New Amsterdam and renamed it after the Duke of York; Colonel Richard Nicolls took over as Governor. Fort Amsterdam was renamed Fort James, for the King’s brother, the Duke of York (and future King).

In late August and early September 1664, British forces took over New Amsterdam, the first of several more or less peaceful changes in power that our ancestors and thier families lived through, living in the same place the whole time but frequently under completely new governments.In the following paragraph there are three of our ancestors mentioned, Tjerck, Evert Pels, and Allert Heymans. In a regular court session on 7 October 1664, Roelof Swartwout, former Schout, and Tjerck have some disputes to settle (Kingston Papers, pp. 163-164). Tjerck wants to be paid for pasturing three cows for Roelof, in a repeat of a demand going back to 29 June. Roelof says he agrees he owes for two cows, but that Tjerck was supposed to pasture two more cows “in payment of the fine due from him,” according to the 29 June agreement. The court refers the matter to the arbitration of Evert Pels and Allert Heymans, “good men.” Then Roelof says that Roelof has legally attached 15 schepels of wheat that belongs to Foppe Barents but is in Tjerck’s possession, but that Tjerck assigned his claim to the wheat to his brother-in-law Jan Tomassen in Fort Orange.

The VAN ETTEN Family

emmigrate from Etten

On January 11, 1665, Jacob Jansen Von Etten married Annetje Arians in Kingston, NY (Kingston Church Records). Since Jacob Jansen had been born in Etten, it was natural for he and Annetje to adopt the name von (from) Etten as a surname. The "von" was soon changed to the English form "Van". Thus began the Van Etten family of America.

The children of Jacob and Annatje grew up and each married a Dutch neighbor. A few remained near home, but others sought their fortune by moving" - The Van Etten Family of America, Leslie Van Etten Oath of Allegiance to England in 1689, in Marble town, NY. First appears in records as "Van Etten" in 1670 when son Adrian, their third child, was baptized. Annetje and Jacobs first child, daughter Tryntje Van Etten was born in 1684 and married her neighbor Evert Ariensen Roosa.

13 May 1664 Aert Pietersen Tack's wife Annetje Ariaens prepares to sell the farm and other personal property to pay off debts “because her husband Aert Pietersen Tack has absented himself.” On 7 October 1664 (Kingston Papers pp. 543-544), the effects of Aert Pietersen Tack are sold at auction in Wildwyck. Aert apparently left town, probably knowing he was broke. He left behind his wife Annetje Ariaens, a house and lot inside the Wildwyck stockade, farmland outside the town wall adjacent to Tjerck’s at the Groot Stuck, and various goods. Tjerck bids on the farmland, but it’s bought by Sweerus Teunissen (1,130 guilders for 20 morgens;

Antony Crispel and Tjerck Claessen De Witt are mentioned in a Kingston paper and I am including it here as it is an interesting interaction between two of our ancestors in 1668.

An entirely different type of house is a building, on a lot, where people live and frequently, particularly in the early days, these were made of wood, essentially they were very large crates, and they could be moved from lot to lot. In real estate transactions: Sometimes a person buys a lot; sometimes a house and lot; sometimes just a house. January 1668/9, in Kingston town council (Kingston Papers, p. 421), when Tierck Claesen complains that Antony Crispel bought “a house, situated across the bridge, for 12 pounds of flax” and never paid for it. Crispel agrees he bought the house, but his impression was that Tjerck would deliver it. Tjerck says the house is across a bridge; moving it is Crispel’s problem.

Antony Crispel's daughter Marie who was one of the captured survivors married Cornelius B Slecht.Hendrickson Family

Early Dutch Explorer

Barent Hendrickse married Neeltze Evertson in 1524. They had four children three of which died in infancy. Thier son Lambert engaged in a sea-faring life and became a famous admiral in the Dutch navy. and was a trusted friend of William the Silent more commonly known in the Netherlands as William of Orange (Dutch: Willem van Oranje), was the leader of the Dutch revolt against the Spanish Habsburgs that set off the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648).

Lambert Hendricksen nicknamed "Pretty Lambert" married a woman of Spanish extraction who was the daughter of Manely Nadal an officier in the army of the Duke of Alva, but still remained a friend of Dutch patriots. They had three daughters but no record of thier lives but their son Daniel lived in Scrool in Holland and was the father of Gerrit who came to America in the ship St Jean Baptiste and landed at New Amsterdam in May 1661. Lambert was present as a rear admiral at the battle of Gibraltar and was active against the Dunkirk corsairs and in 1605 managed to defeat and capture the Dunkirk admiral Adriaan Dirksen.

From 1616 to 1624, Lambert was mostly active in the Mediterranean to protect Dutch merchants from the Barbary pirates, and fighting in the Dutch-Barbary war (1618-1622). In 1618 teamed up with the Spanish to defeat the Algerian corsair fleet. In 1622, he negotiated a peace agreement with the Pasha of Algiers to leave Dutch merchant shipping unmolested. After this treaty was broken by the Algerians, Lambert was sent to take punitive action against the Barbary pirates and through harsh negotiations managed to force the Algerians to set hundreds of Christian slaves free.

Cornelus, the elder of son of Lambert Hendricksen was born at Utrecht, in 1572, became a navigator, and was the first man to set foot on the soil of Pennsylvania and West Jersey. He was the discoverer of the Raritan and Schuylkill rivers, and explored the Delware to the falls, at the present site of Trenton. During the latter part of 1614, he explored the coast of New Jersey, in the Yacht "Onrest" the first vessel built in New Amsterdam.

https://www.familysearch.org/photos/artifacts/13853631?cid=mem_copy